Permafungi is the realisation of a somewhat crazy challenge: to recycle some of the 7 billion tonnes of coffee grounds produced worldwide each year. Once collected and processed, these coffee grounds are used as a substrate for growing oyster mushrooms, but also for producing a myco-material.

For several years now, the Brussels-based PermaFungi project, already fully invested in the production of edible mushrooms, has also been transforming ‘champost’ (the residue from oyster mushroom cultivation) into a sustainable and biodegradable material by adding mycelium, the seed of the mushroom. This innovation has led to the recent opening of a second production site and the growing presence of this myco-material in upcoming design projects. We met Julien Jacquet, CEO of this extraordinary project, which is set to become ‘the norm’.

What is striking about this project is that, at the outset, people might have thought you were mad.

That was the case. We were true idealists, convinced that we could create a new business model. When we started the project in 2014, we collected nearly 100 kilos of coffee grounds per day by bicycle. We didn’t keep up that pace for very long, but it’s a good indicator of our level of commitment. Since our beginnings in the cellars of Tour & Taxis (one of our two production sites in Brussels, the second being located in Forest, editor’s note), our goal has not changed: to connect people and nature by recovering waste that we bring back into our ecosystem through edible mushrooms (oyster mushrooms and shiitakes), among other things. We have overcome many obstacles, including scepticism from professionals in the mushroom sector, as well as certain rules that prohibited growing mushrooms on coffee grounds, for example.

Between edible mushrooms and Lionel Jadot’s project for the Jam Hotel in Ghent, which opened in September 2025, you can’t say the connection is obvious. When and how did you come up with the idea of creating objects?

Our business model is based on our desire to create jobs. We started out with six people and now there are 12 of us working on the project. The move into design came from our desire to prove that our idealism could become a profitable and virtuous pursuit. In 2017, we identified the possibility of creating a myco-material based on the same principle as for edible mushrooms. We first created packaging that is a more sustainable and aesthetic alternative to plastic. We then expanded on this ‘bespoke’ approach.

Your first lamps have been installed in the Entropy restaurant in Brussels, among other venues.

The people who come to us are sensitive to the very particular aesthetics of mycelium, like us. It’s a natural material that we refuse to dye, even when asked. The white colour and the nuances found on the surface are due solely to natural phenomena.

This aesthetic also appealed to designer Lionel Jadot, who ordered hundreds of pendant lights for the Jam Hotel in Ghent (Belgium).

We were put in touch through Natura Mater (an organisation that supports construction professionals in selecting and using sustainable materials, editor’s note). It was love at first sight for both sides. Unlike our first lamps, which were only 30 centimetres in diameter, these required real research. To obtain these large hexagons, we had to create moulds that respected the constraints of the material and find the right amount of substrate while meeting Lionel Jadot’s requirements. We also wanted to avoid producing unnecessary moulds by reusing existing models as much as possible.

You had already collaborated with Lionel Jadot on the Cohabs co-living project in Brussels, but your various collaborations also include some rather spectacular panels for the Belgian pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2023.

This project emerged from our meeting with the curator Vinciane Despret. In collaboration with the Bento collective of architects, she entrusted us with the creation of no fewer than 700 panels made of myco-material that framed a raw earth floor. The result was almost mystical.

Would you say that your development strategy is influenced by nature?

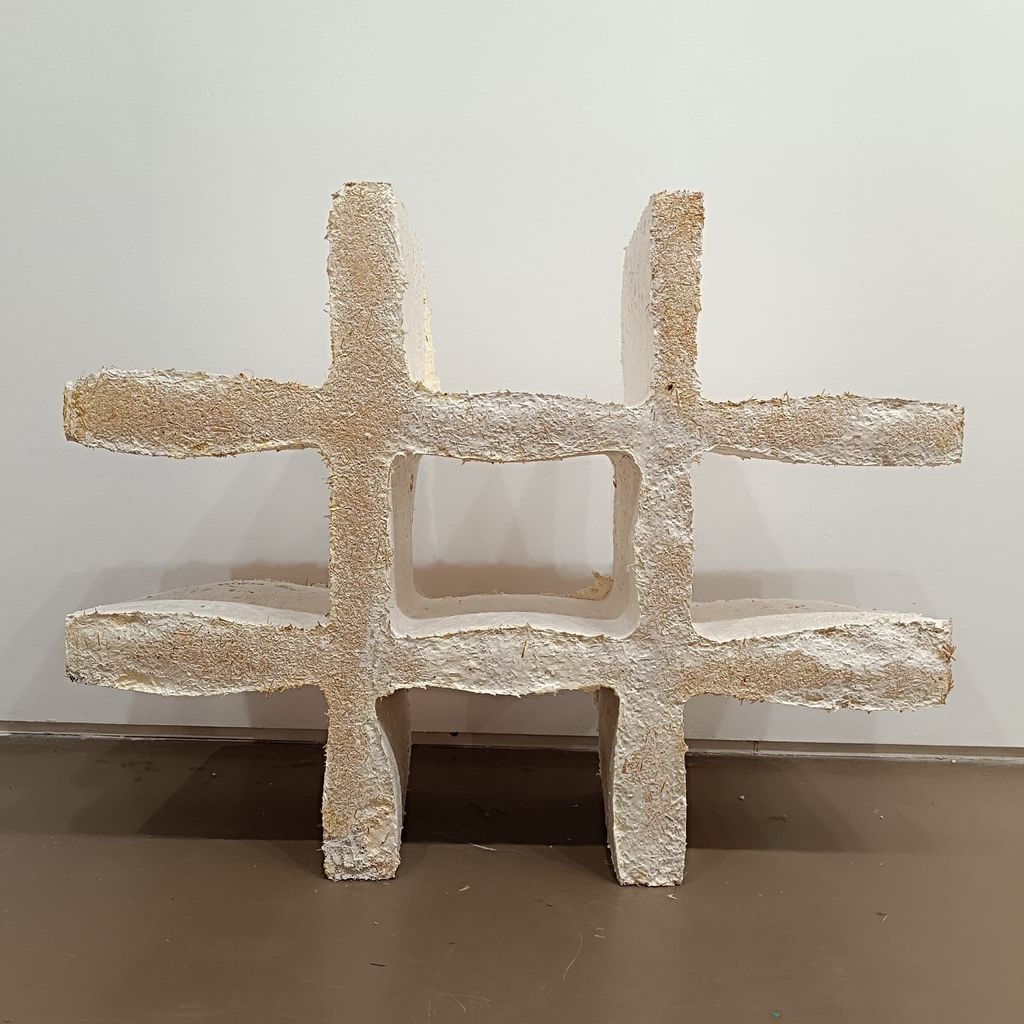

Our creativity and that of our partners has no limits, except those dictated by nature. Apart from bowing to this constraint, we can do anything. Recently, we developed a stool project with Domingo (a design studio created by Belgians based in Barcelona, editor’s note) and a room divider with Sonian Wood Project, a company that works with wood from the Sonian Forest.