The stables of CID Grand-Hornu are being transformed to host the work of Patricia Urquiola, a designer from Oviedo who is now based in Milan, where she serves as the artistic director for Cassina.

Surprising and fantastical, the ‘Patricia Urquiola. Meta-morphosa’ exhibition (on display until 26 April) is the result of the multilingual artist being given carte blanche. Combining craftsmanship and industry, she showcases her most recent furnishings and pieces for major brands, as well as projects from outside the industrial sphere. We ask the designer, as well as the venue director Marie Pok, about the aesthetic of transformation that runs through this event.

What was the jumping-off point for your collaboration?

Marie Pok: It all started with observing Patricia’s work. The exhibition was reshaped and defined gradually and the working process became the theme itself: a true transformation.

Patricia Urquiola: Our method of working was based on constant dialogue and gave way to the title ‘Meta-morphosa’, which is composed of the prefix ‘meta’, which means ‘beyond’, and a variant of ‘morphosis’, which refers to a change in form. This exhibition is also a love letter from me to Metamorphoses by the philosopher Emanuele Coccia. A book that encourages us to expand our relationship to humanity and living beings, and which was very important to me during Covid thanks to its beautiful message.

Patricia, how does your exhibition interact with CID Grand-Hornu?

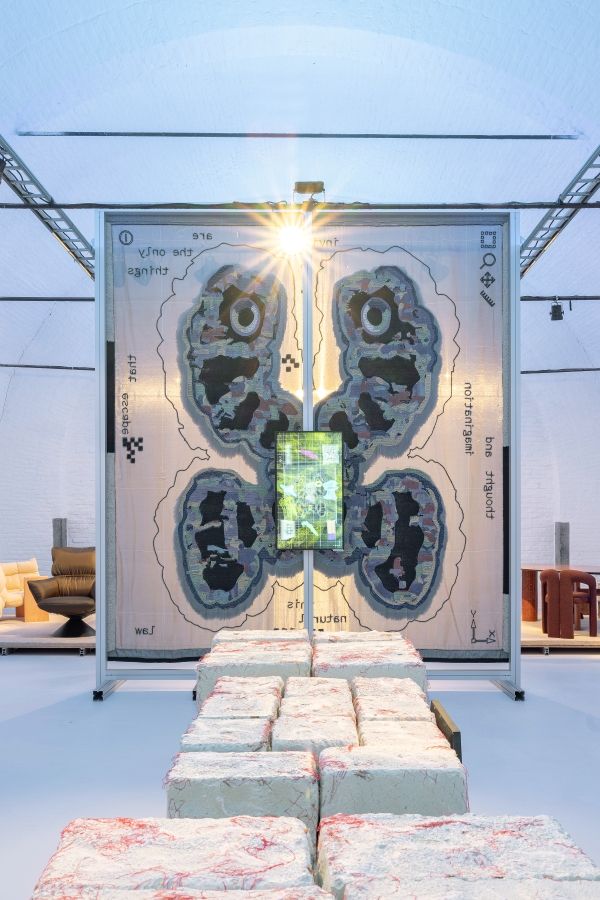

My roots are in Asturias in Spain, a mining region. Arriving at the Grand-Hornu, I was met by familiar sights: slag heaps, bricks, etc. For me, the spirit of the place is key. What I like about this place is that the traditional feeling of a white cube is gone. The space has a geography of its own. You enter via the centre of the exhibition space. You can move about freely and there is no set route you need to follow to understand. The first piece you see, Mushmonster – a giant textile piece made from Polimex, an ultra-lightweight upholstery fabric, and a water-based printed fabric – speaks for itself. It is neither an object nor a work of art.

What do you want the visitor to feel as they browse the exhibition, intellectually or physically?

I think my work focuses on the concept of transformation. I hope visitors will feel the sense of opening up that my projects and creations evoke. To accentuate this feeling, we wanted to experiment with the staging using a blue light, which makes the space feel more abstract and less real. A light that transports us to a timeless place, a place of metamorphosis. Chenille y Papillon, the two tufted tapestries which are displayed on either side of the exhibition, evoke this state of transition.

Marie, what challenges did you face recreating this approach in the space?

The main issue was really the lighting. We needed to create a sense of harmony between the blue light (to evoke a feeling) and the spotlights on the pieces themselves (that make them easy to see). In the beginning, the two lights were clashing. It takes a great lighting designer to find this balance, in order to make the exhibition feel like a refuge where you feel comfortable.

Patricia, the exhibition evokes the idea of change. In an ever-changing world, how do you define evolution?

Evolving means staying open to the progress that different processes and changes can bring about. One of the current issues is that there will be much fewer materials to use in the future. We will have to produce new natural materials that can be regenerated. That’s the only way in which industry can evolve in a virtuous manner.

How do you stay optimistic about creating?

You can’t move forward in this world if you’re not an optimist. But maybe optimists are the ones who push forward? I feel more like Saint Anthony in the desert. I need to create my “Thebaid”, a safe space, to create a workspace where I can connect with life’s problems. That’s what we have recreated in the exhibition: my mental cocoon. The final room, which was created in collaboration with Emanuele Coccia, showcases many hybrid objects that represent a metaphor for learning.

Is artificial intelligence just a technical tool for you, or is it a creative partner in its own right?

PU: It’s a language that is being integrated into my research little by little, without my team and I becoming too dependant on this tool.

MP: In the exhibition, it would be easy to think that the Gruuvelot modular sofa was created using AI. But in reality, Patricia designed it in a very intuitive way.

PU: I don’t make a distinction between high tech and artisan. For example, the design of the Chenille y Papillon rugs was done on a computer, but we tweaked the settings of the robots to obtain unusual shapes.

Marie, as the director of CID Grand-Hornu, how do you view this departure from traditional industrial design?

The furniture industry is undergoing a shift, and one of the roles of the designer is to support its transition towards a more responsible form of production. What’s incredible about this exhibition is how all-powerful imagination is. We didn’t expect Patricia Urquiola to go where she has, in a very personal direction. It’s a liberation of her interior world, far removed from the standard rules of industrial design.

Patricia, the exhibition focuses on your projects and research from the past five years. How do you reconcile industrial production with the environmental concerns of our era?

It’s a constant dialogue – and at times, fight – with all of the professions in the industry. I often go to manufacturers and disrupt the established dialogue. For example, with glass-blowers, I say: ‘Come on, let’s make the paste with leftovers!’ At Cassina, which is a very complex company, a lot of work is done on the invisible part of the furniture. Before, they moulded the foam onto the structure. Now, they separate the structure from the upholstery and use recycled foam.

What does ‘beauty’ mean to you?

PU: It’s anti-perfectionism because perfection robs us of our strength as human beings. Today, though, beauty also means breathing new life into a material. Circularity.

MP: For this exhibition, beauty is defined by the imagination, which becomes a tool used to experiment and navigate the complexity of the world around us.

Patricia, you were famously trained by two Italian masters: Achille Castiglioni and Vico Magistretti. How is that training reflected in this exhibition?

Castiglioni taught me to design an exhibition as a story. I broke from that a little here because the space allows visitors to enter through the centre, but the desire to tell a story remains. Magistretti succeeded in industrialising the artisanal armchair. Today, we need to reconsider this legacy. In the exhibition, this concept of transmission is represented by a talisman and a boat, which are symbols of perseverance. There is no designer without perseverance.

If you had to select one object from this exhibition that foreshadows the design of the future, which object would you choose?

MP: It would be the tapestry displayed in the Thebaid room, no question. The centre was made by a machine, but Patricia has attached edges that were hand-embroidered by a community of women in rural India. That’s the future: not choosing between technology and craftsmanship, but combining them.

PU: Yeah, it’s understanding that our design ecosystem always needs to be considered with an open mind, by combining expertise from all over the world.